Boltzmann's entropy formula

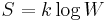

In statistical thermodynamics, Boltzmann's equation is a probability equation relating the entropy S of an ideal gas to the quantity W, which is the number of microstates corresponding to a given macrostate:

(1)

(1)

where k is Boltzmann's constant equal to 1.38062 x 10−23 joule/kelvin and W is the number of microstates consistent with the given macrostate.

"Log" is the natural logarithm,so the formula can also be notated as:

In short, the Boltzmann formula shows the relationship between entropy and the number of ways the atoms or molecules of a thermodynamic system can be arranged. In 1934, Swiss physical chemist Werner Kuhn successfully derived a thermal equation of state for rubber molecules using Boltzmann's formula, which has since come to be known as the entropy model of rubber.

Contents |

History

The equation was originally formulated by Ludwig Boltzmann between 1872 to 1875, but later put into its current form by Max Planck in about 1900.[2][3] To quote Planck, "the logarithmic connection between entropy and probability was first stated by L. Boltzmann in his kinetic theory of gases."

The value of  was originally intended to be proportional to the Wahrscheinlichkeit (the German word for probability) of a macroscopic state for some probability distribution of possible microstates — the collection of (unobservable) "ways" the (observable) thermodynamic state of a system can be realized by assigning different positions and momenta to the various molecules. Interpreted in this way, Boltzmann's formula is the most general formula for the thermodynamic entropy. However, Boltzmann’s paradigm was an ideal gas of

was originally intended to be proportional to the Wahrscheinlichkeit (the German word for probability) of a macroscopic state for some probability distribution of possible microstates — the collection of (unobservable) "ways" the (observable) thermodynamic state of a system can be realized by assigning different positions and momenta to the various molecules. Interpreted in this way, Boltzmann's formula is the most general formula for the thermodynamic entropy. However, Boltzmann’s paradigm was an ideal gas of  identical particles, of which

identical particles, of which  are in the

are in the  -th microscopic condition (range) of position and momentum. For this case, the probability of each microstate of the system is equal, so it was equivalent for Boltzmann to calculate the number of microstates associated with a macrostate.

-th microscopic condition (range) of position and momentum. For this case, the probability of each microstate of the system is equal, so it was equivalent for Boltzmann to calculate the number of microstates associated with a macrostate.  was historically misinterpreted as literally meaning the number of microstates, and that is what it usually means today.

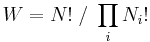

was historically misinterpreted as literally meaning the number of microstates, and that is what it usually means today.  can be counted using the formula for permutations

can be counted using the formula for permutations

(2)

(2)

where i ranges over all possible molecular conditions and  denotes factorial. The "correction" in the denominator is due to the fact that identical particles in the same condition are indistinguishable.

denotes factorial. The "correction" in the denominator is due to the fact that identical particles in the same condition are indistinguishable.  is sometimes called the "thermodynamic probability" since it is an integer greater than one, while mathematical probabilities are always numbers between zero and one.

is sometimes called the "thermodynamic probability" since it is an integer greater than one, while mathematical probabilities are always numbers between zero and one.

Generalization

Boltzmann's formula applies to microstates of the universe as a whole, each possible microstate of which is presumed to be equally probable.

But in thermodynamics it is important to be able to make the approximation of dividing the universe into a system of interest, plus its surroundings; and then to be able to identify the entropy of the system with the system entropy in classical thermodynamics. The microstates of such a thermodynamic system are not equally probable—for example, high energy microstates are less probable than low energy microstates for a thermodynamic system kept at a fixed temperature by allowing contact with a heat bath.

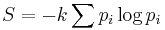

For thermodynamic systems where microstates of the system may not have equal probabilities, the appropriate generalization, called the Gibbs entropy, is:

(3)

(3)

This reduces to equation (1) if the probabilities pi are all equal.

Boltzmann used a  formula as early as 1866.[4] He interpreted

formula as early as 1866.[4] He interpreted  as a density in phase space—without mentioning probability—but since this satisfies the axiomatic definition of a probability measure we can retrospectively interpret it as a probability anyway. Gibbs gave an explicitly probabilistic interpretation in 1878.

as a density in phase space—without mentioning probability—but since this satisfies the axiomatic definition of a probability measure we can retrospectively interpret it as a probability anyway. Gibbs gave an explicitly probabilistic interpretation in 1878.

Boltzmann himself used an expression equivalent to (3) in his later work[5] and recognized it as more general than equation (1). That is, equation (1) is a corollary of equation (3)—and not vice versa. In every situation where equation (1) is valid, equation (3) is valid also—and not vice versa.

Boltzmann entropy excludes statistical dependencies

The term Boltzmann entropy is also sometimes used to indicate entropies calculated based on the approximation that the overall probability can be factored into an identical separate term for each particle—i.e., assuming each particle has an identical independent probability distribution, and ignoring interactions and correlations between the particles. This is exact for an ideal gas of identical particles, and may or may not be a good approximation for other systems.[6]

See also

References

- ^ See: photo of Boltzmann's grave in the Zentralfriedhof, Vienna, with bust and entropy formula.

- ^ Boltzmann equation – Eric Weisstein’s World of Physics (states the year was 1872)

- ^ Perrot, Pierre (1998). A to Z of Thermodynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856552-6. (states the year was 1875)

- ^ Ludwig Boltzmann (1866). "Über die Mechanische Bedeutung des Zweiten Hauptsatzes der Wärmetheorie". Wiener Berichte 53: 195–220.

- ^ Ludwig Boltzmann (1896 and 1898). Vorlesungen über Gastheorie. J.A. Barth, Leipzig.

- ^ Jaynes, E. T. (1965). Gibbs vs Boltzmann entropies. American Journal of Physics, 33, 391-8.